Ka Mua, Ka Muri: Half a Century of Te Reo Māori

In times of uncertainty, it can feel as though progress is out of reach. Current government policies, societal pressures, and everyday challenges often make the path forward seem daunting. Yet history shows us that hope is not just possible—it is built when people stand together. As the whakataukī reminds us, Ka mua, ka muri – we walk backwards into the future, guided by the courage and wisdom of those who came before us.

Honouring the Past: The Māori Language Petition

Language is more than words—it is identity, culture, and resistance.

The Māori Language Petition

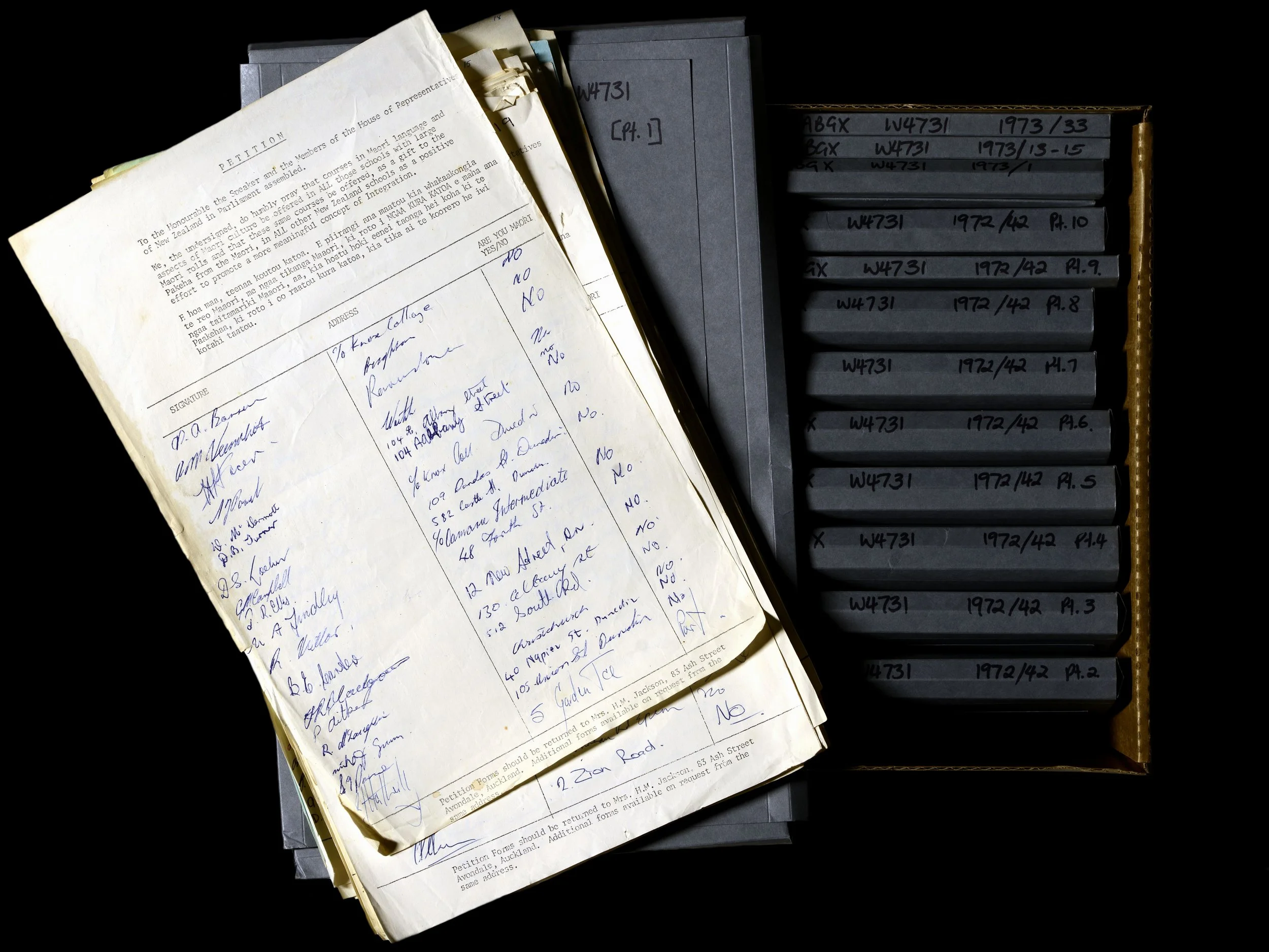

In 1972, the Māori language petition became a defining moment for te reo Māori. At a time when Māori children were punished for speaking their language in schools, and public life largely ignored it, thousands of New Zealanders united to demand recognition.

The campaign was led not by a single figure but by young Māori activists: Auckland-based Ngā Tamatoa (“The Young Warriors”) and Te Reo Māori Society at Victoria University of Wellington. These student-led groups collected more than 30,000 signatures, and in September 1972 they delivered the petition to Parliament, calling for te reo to be taught in schools. Their action proved that ordinary people, acting collectively, could compel the government to listen.

While the petition itself was youth-led, the early 1970s also saw figures such as Dame Whina Cooper gathering momentum around Māori rights more broadly. Three years later she would lead the 1975 Māori Land March, drawing national attention to land alienation and uniting diverse groups behind a common cause. Together, these movements signalled a new era of Māori activism and showed how voices from different generations could converge to create change.

The petition was not just about language—it was about identity, dignity, and recognition. Its youth leadership reminds us that when people mobilise, extraordinary change is possible.

The Journey: From Petition to Progress

From a single petition to a nationwide movement, the revival of te reo Māori tells a story of community action becoming national change. Within a decade whānau had opened the first kōhanga reo (1982) and kura kaupapa Māori (from 1985), and in 1987 the Māori Language Act granted te reo official status and created Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori.

In the 1990s and 2000s Māori-language media blossomed: iwi radio stations spread nationwide, Waka Huia preserved tribal knowledge on television, the country celebrated “Māori Language Year” in 1995, Dame Hinewehi Mohi sang the national anthem in te reo at the 1999 Rugby World Cup, and Māori Television launched in 2003. More than 800 kōhanga reo operated by the mid-1990s, supported by new Māori-medium teacher training and university courses.

In recent years the revival has become increasingly visible: schools and workplaces celebrate Te Wiki o te Reo Māori, companies such as The Warehouse integrate te reo into marketing campaigns, councils roll out bilingual signage, and popular culture and social media showcase music, film and content in Māori. These achievements show that te reo is living, evolving and relevant.

Every signature, every kōhanga reo, every bilingual sign is a statement: we do not forget, and we will continue.

The Power of the People Today

History teaches a crucial lesson: change is made by people, not policy alone. The revitalisation of te reo Māori and the protection of Māori rights depend on communities and individuals choosing to act. Every effort matters—from teaching a child a simple greeting in te reo, to playing a game of pūkana, to incorporating Māori phrases into classrooms or workplaces. These everyday actions, small as they may seem, are the heartbeat of revitalisation.

Dame Whina Cooper, who led the 1975 Māori Land March, showed the country how collective action can shift the national conversation. That truth has been carried forward by many. Dame Iritana Tawhiwhirangi spearheaded the kōhanga reo movement, nurturing new generations of fluent speakers. Moana Jackson’s tireless advocacy reshaped how Aotearoa understands Māori rights and constitutional transformation. Tāme Iti has long stood as a fearless activist, insisting that Māori voices be heard in both local and global arenas. More recently, Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke’s haka in Parliament reminded the nation that the fight for mana is alive in the next generation, while Eru Kapa-Kingi’s leadership of the Toitū te Tiriti hīkoi shows the power of collective action today.

The 2024 Hikoi to Parliament

Each of these figures stands in the same whakapapa of action and courage: proof that change is made not by waiting, but by acting. And alongside these leaders, every person who chooses to speak, teach, or celebrate te reo contributes to a movement capable of shifting societal attitudes and creating lasting impact.

Policy changes alone cannot protect our culture – only people can.

Walking Forward: Hope and Action

Ka mua, ka muri urges reflection as we step into the future. We walk backwards, learning from the courage and commitment of those who came before us. Revitalising te reo Māori is not a symbolic gesture, it is a declaration that identity, culture, and heritage matter.

The message is clear: we do it again. Not because the work is easy, but because hope, pride, and collective action are stronger than complacency or despair.

Check out our sources for this article to learn more about the history of Te Wiki o te Reo Māori: